Pitfalls of linear sample reduction: Part 4

31 Jul 2019A quick recap: animation clips are formed from a set of time series called tracks. Tracks have a fixed number of samples per second and each track has the same length. The Animation Compression Library retains every sample while Unreal Engine uses the popular method of removing samples that can be linearly interpolated from their neighbors.

The first post showed how removing samples negates some of the benefits that come from segmenting, rendering the technique a lot less effective.

The second post explored how sorting (or not) the retained samples impacts the decompression performance.

The third post took a deep dive into the memory overhead of the three techniques we have been discussing so far:

- Retaining every sample with ACL

- Sorted and unsorted linear sample reduction

This fourth and final post in the series shows exactly how many samples are removed in practice.

How often are samples removed?

In order to answer this question, I instrumented the ACL UE4 plugin to extract how many samples per pose, per clip, and per track were dropped. I then ran this over the Carnegie-Mellon University motion capture database as well as Paragon and Fortnite. I did this while keeping every sample with full precision (quantizing the samples can only make things worse) with and without error compensation (retargeting). The idea behind retargeting is to compensate the error by altering the samples slightly as we optimize a bone chain. While it will obviously be slower to compress than not using it, it should in theory reduce the overall error and possibly allow us to remove more samples as a result.

Note that constant and default tracks are ignored when calculating the number of samples dropped.

| Carnegie-Mellon University | With retargeting | Without retargeting |

|---|---|---|

| Total size | 204.40 MB | 204.40 MB |

| Compression speed | 6487.83 KB/sec | 9756.59 KB/sec |

| Max error | 0.1416 cm | 0.0739 cm |

| Median dropped per clip | 0.13 % | 0.13 % |

| Median dropped per pose | 0.00 % | 0.00 % |

| Median dropped per track | 0.00 % | 0.00 % |

As expected, the CMU motion capture database performs very poorly with sample reduction. By its very nature, motion capture data can be quite noisy as it comes from cameras or sensors.

| Paragon | With retargeting | Without retargeting |

|---|---|---|

| Total size | 575.55 MB | 572.60 MB |

| Compression speed | 2125.21 KB/sec | 3319.38 KB/sec |

| Max error | 80.0623 cm | 14.1421 cm |

| Median dropped per clip | 12.37 % | 12.70 % |

| Median dropped per pose | 13.04 % | 13.41 % |

| Median dropped per track | 2.13 % | 2.25 % |

Now the data is more interesting. Retargeting continues to be slower to compress but surprisingly, it fails to reduce the memory footprint as well as the number of samples dropped. It even fails to improve the compression accuracy.

| Fortnite | With retargeting | Without retargeting |

|---|---|---|

| Total size | 1231.97 MB | 1169.01 MB |

| Compression speed | 1273.36 KB/sec | 2010.08 KB/sec |

| Max error | 283897.4062 cm | 172080.7500 cm |

| Median dropped per clip | 7.11 % | 7.72 % |

| Median dropped per pose | 10.81 % | 11.76 % |

| Median dropped per track | 15.37 % | 16.13 % |

The retargeting trend continues with Fortnite. One possible explanation for these disappointing results is that error compensation within UE4 does not measure the error in the same way that the engine does after compression is done: it does not take into account virtual vertices or leaf bones. This discrepancy leads to the optimizing algorithm thinking the error is lower than it really is.

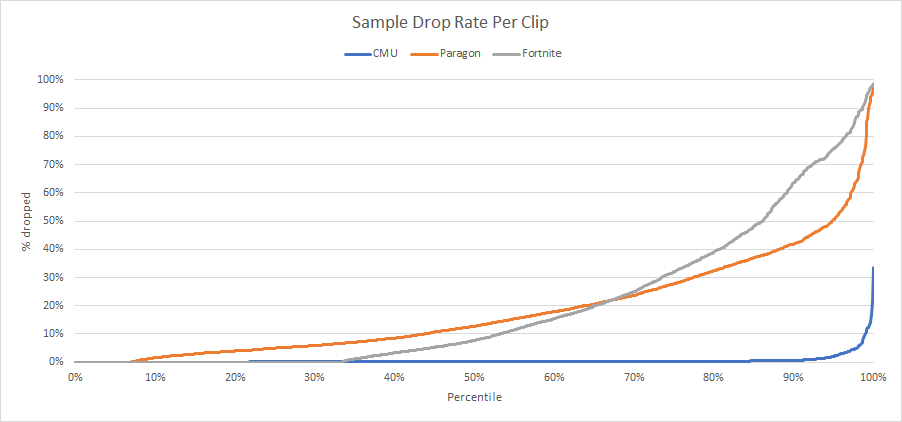

This is all well and good but how does the full distribution look? Retargeting will be omitted since it doesn’t appear to contribute much.

Note that Paragon and Fortnite have ~460 clips (7%) and ~2700 clips (32%) respectively with one or two samples and thus no reduction can happen in those clips.

The graph is quite telling: more often than not we fail to drop enough samples to match ACL with segmenting. Very few clips end up dropping over 35% of their samples: none do in CMU, 18% do in Paragon, and 23% in Fortnite.

This is despite using very optimistic memory overhead estimates. In practice, the overhead is almost always higher than what we used in our calculations and removing samples might negatively impact our quantization bit rates, further increasing the overall memory footprint.

Note that curve fitting might allow us to remove more samples but it would slow down compression and decompression.

Removing samples just isn’t worth it

I have been implementing animation compression algorithms in one form or another for many years now and I have grown to believe that removing samples just isn’t worth it: retaining every sample is the overall best strategy.

Games often play animations erratically or in unpredictable manner. Some randomly seek while others play forward and backward. Various factors control when and where an animation starts playing and when it stops. Clips are often sampled at various sample rates that differ from their runtime playback rates. The ideal default strategy must handle all of these cases equally well. The last thing animators want to do is mess around with compression parameters of individual clips to avoid an algorithm butchering their work.

When samples are removed, sorting what is retained and using a persistent context is a challenging idea in large scale games. Even if decompression has the potential to be the fastest under specific conditions, in practice the gains might not materialize. Regardless, whether the retained samples are sorted or not, metadata must be added to compensate and it eats away at the memory gains achieved. While the Unreal Engine codecs (which use unsorted sample reduction) could be optimized, the amount of cache misses cannot be significantly reduced and ultimately proves to be the bottleneck.

Furthermore, as ACL continues to show, removing samples is not necessary in order to achieve a low and competitive memory footprint. By virtue of having its data simply laid out in memory, very little metadata overhead is required and performance remains consistent and lightning fast. This also dramatically simplifies and streamlines compression as we do not need to consider which samples to retain while attempting to find the optimal bit rate for every track.

It is also worth noting that while we assumed that it is possible to achieve the same bit rates as ACL while removing samples, it might not be the case as the resulting error will combine in subtle ways. Despite being very conservative in our estimates with the sample reduction variants, ACL emerges a clear winner.

That being said, I do have some ideas of my own on how to tackle the problem of efficient sample reduction and maybe someday I will get the chance to try them even if only for the sake of research.

A small note about curves

It is worth nothing that by uniformly sampling an input curve, some amount of precision loss can happen. If the apex of a curve happens between two samples, it will be smoothed out and lost.

The most common curve formats (cubic) generally require 4 values in order to interpolate. This means that the context footprint also increases by a factor of two. In theory, a curve might need fewer samples to represent the same time series but that is not always the case. Animations that come from motion capture or offline simulations such as cloth or hair will often have very noisy data and will not be well approximated by a curve. Such animations might see the number of samples removed drop below 10% as can be seen with the CMU motion capture database.

Curves might also need arbitrary time values that do not fall on uniformly distributed values. When this is the case, the time cannot be quantized too much as it will lower the resulting accuracy, further complicating things and increasing the memory footprint. If the data is non-uniform, a context object is required in order to keep decompression fast and everything I mentioned earlier applies. This is also true of techniques that store their data relative to previous samples (e.g. a delta or velocity change).

Special thanks

I spend a great deal of time implementing ACL and writing about the nuggets of knowledge I find along the way. All of this is made possible, in part, thanks to Epic which is generously allowing me to use the Paragon and Fortnite animations for research purposes. Cody Jones, Martin Turcotte, and Raymond Barbiero continue to contribute code, ideas, and proofread my work and their help is greatly appreciated. Many others have contributed to ACL and its UE4 plugin as well. Thank you for keeping me motivated and your ongoing support!