Animation Compression: Linear Key Reduction

07 Dec 2016With simple key quantization, if we needed to sample a certain time T for which we did not have a key (e.g. in between two existing keys), we linearly interpolated between the two.

A natural extension of this is of course to remove keys or key frames which can be entirely linearly interpolated from their neighbour keys as long as we introduce minimal or no visible error.

How It Works

The process to remove keys is fairly straight forward:

- Pick a key

- Calculate the value it would have if we linearly interpolated it from its neighbours

- If the resulting track error is acceptable, remove it

The above algorithm continues until nothing further can be removed. How you pick keys may or may not impact significantly the results. I personally only ever came across implementations that iterated on all keys linearly forward in time. However, in theory you could iterate in any number of ways: random, key with smallest error first, etc. It would be interesting to try various iteration methods.

It is worth pointing out that you need to check the error at a higher level than the individual key you are removing since it might impact other removed keys by changing the neighbour used to remove them. As such you need to look at your error metric and not just the key value delta.

Removing keys is not without side effects: now that our data is no longer uniform, calculating the proper interpolation alpha to reconstruct our value at time T is no longer trivial. To be able to calculate it, we must introduce in our data a time marker per remaining key (or key frame). This marker of course adds overhead to our animation data and while in the general case it is a win, memory wise, it can increase the overall size if the data is very noisy and no or very few keys can be removed.

A simple formula is then used to reconstruct the proper interpolation alpha:

TP = Time of Previous key

TN = Time of Next key

Interpolation Alpha = (Sample Time - TP) / (TN - TP)

Another important side effect in introducing time markers is that when we sample a certain time T, we must now search to find between which two keys we must interpolate. This of course adds some overhead to our decompression speed.

The removal is typically done in one of two ways:

- Removal of whole key frames that can be linearly interpolated

- Removal of independent keys that can be linearly interpolated

While the first is less aggressive and will generally yield a higher memory footprint, the decompression speed will be faster due to needing to search only once to calculate our interpolation alpha.

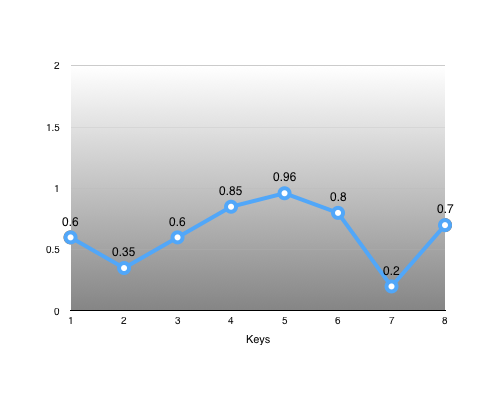

For example, suppose we have the following track and keys:

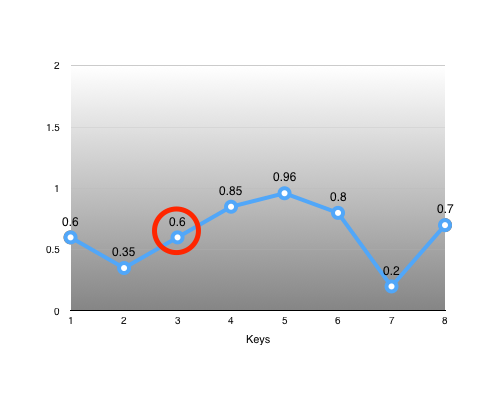

The key #3 is of particular interest:

As we can see, we can easily recover the interpolation alpha from its neighbours: alpha = (3 - 2) / (4 - 2) = 0.5. With it, we can perfectly reconstruct the missing key: value = lerp(0.35, 0.85, alpha) = 0.6.

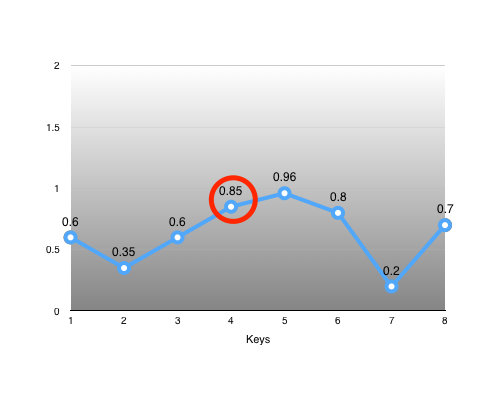

Another interesting key is #4:

It lies somewhat close to the value we could linearly interpolate from its neighbours: value = lerp(0.6, 0.96, 0.5) = 0.78. Whether the error introduced by removing it is acceptable or not is determined by our error metric function.

In The Wild

This algorithm is perhaps the most common and popular out there. Both Unreal 4 and Unity 5 as well as many popular game engines support this format. They all use slight variations mostly in their error metric function but the principle remains the same. Sadly most implementations out there tend to use a poorly implemented error metric which tends to yield bad results in many instances. This typically stems from using a local error metric where each track type has a single error threshold. Of course the problem with this is that due to the hierarchical nature of our bone data, some bones need higher accuracy (e.g. pelvis, root). Some engines mitigate this by allowing a threshold per track or per bone but this requires some amount of tweaking to get right which is often undesirable and sub-optimal.

Twice in my career I had to implement a new animation compression algorithm and both times were to replace bad linear key reduction implementations.

From the implementations I have seen in the wild, it seems more popular to remove individual keys as opposed to removing whole key frames.

Performance

Sadly due to the loss of data uniformity, the cache locality of the data we need suffers. Unlike for simple key quantization, we can no longer simply sort by key frame if we remove individual keys (you still can if you remove whole key frames though) to keep things cache efficient.

Although I have not personally witnessed it, I suspect it should be possible to use a variation of a technique used by curve fitting to sort our data in a cache friendly way. It is well described here and we’ll come back to it when we cover curve fitting.

The need to constantly search for which neighbour keys to use when interpolating quickly adds up since it scales poorly. The longer our clip is, the wider the range we need to search and the more tracks we have also increases the amount of searching that needs to happen. I have seen two ways to mitigate this: partitioning our clip or by using a cursor.

Partitioning our clip data as we discussed with uniform segmenting helps reduce the range to search in as our clip length increases. If the number of keys per block is sufficiently small, searching can be made very efficient with a sorting network or similar strategy. The use of blocks will also decrease the need for precision in our time markers by using a similar form of range reduction which allows us to use fewer bits to store them.

Using a cursor is conceptually very simple. Most clips play linearly and predictably (either forward or backward in time). We can leverage this fact to speed up our search by caching which time we sampled last and which neighbour keys were used to kickstart our search. The cursor overhead is very low if we remove whole key frames but the overhead is a function of the number of animated tracks if we remove individual keys.

Note that it is also quite possible that by using the above sorting trick that it could speed up the search but I cannot speak to the accuracy of this statement at this time.

Even though we can reach a smaller memory footprint with linear key reduction compared to simple key quantization, the amount of cache lines we’ll need to touch when decompressing is most likely going to be higher. Along with the need to search for key neighbours, these facts makes it slower to decompress using this algorithm. It remains popular due to the reduced memory footprint which was very important on older consoles (e.g. PS2 and PS3 era) as well as due to its obvious simplicity.

See the following posts for more details: