Arithmetic Accuracy and Performance

29 Dec 2017As I mentioned in my previous post, ACL still suffers from some less then ideal accuracy in some exotic situations. Since the next release will have a strong focus on fixing this, I wanted to investigate using float64 and fixed point arithmetic. It is general knowledge that float32 arithmetic incurs rounding and can lead to severe accuracy loss in some cases. The question I hoped to answer was whether or not this had a significant impact on ACL. Originally ACL performed the compression entirely with float64 arithmetic but this was removed because it caused more issues than it was worth but I did not publish numbers to back this claim up. Now we revisit it once and for all.

To this end, the first research branch was created. Research branches will play an important role in ACL. Their aim is to explore small and large ideas that we might not want to support in their entirety in the main branches while keeping them close. Unless otherwise specified, research branches will not be actively maintained. Once their purpose is complete, they will live on to document what worked and didn’t work and serve as a starting point for anyone hoping to investigate them further.

float64 vs float32 arithmetic

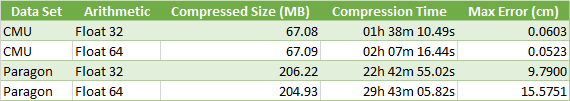

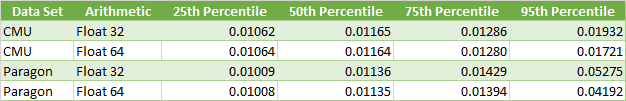

In order to fully test float64 arithmetic, I templated a few things to abstract the arithmetic used between float32 and float64. This allowed easy conversion and support of both with nearly the same code path. The results proved somewhat underwhelming:

As it turns out, the small accuracy loss from float32 arithmetic has a barely measurable impact on the memory footprint for CMU and a 0.6% reduction for Paragon. However, the compression (and decompression) time is much faster.

With float64, the max error for CMU and Paragon is slightly improved for the majority of the clips but not by a significant margin and 4 exotic Paragon clips end up with a worse error.

Consequently, it is my opinion that float32 is the superior choice between the two. The small increase in accuracy and reduction in memory footprint is not significant enough to outweigh the degradation of the performance. Even though the float64 code path isn’t as optimized, it will remain slower due to the individual instructions being slower and the increased number of registers needed. It’s possible the performance might be improved considerably with AVX and so this is something we’ll keep in mind going forward.

Fixed point arithmetic

Another popular alternative to floating point arithmetic is fixed point arithmetic. Depending on the situation it can yield higher accuracy and depending on the hardware it can also be faster. Prior to this, I had never worked with fixed point arithmetic. There was a bit of a learning curve but it proved intuitive soon enough.

I will not explain in great detail how it works but intuitively, it is the same as floating point arithmetic minus the exponent part. For our purposes, during the decompression (and part of the compression), most of the values we work with are normalized and unsigned. This means that the range is known ahead of time and fixed which makes it a good candidate for fixed point arithmetic.

Sadly, it differs so much from floating point arithmetic that I could not as easily support it in parallel with the other two. Instead, I created an arithmetic_playground and tried a whole bunch of things within.

I focused on reproducing the decompression logic as close as possible. The original high level logic to decompress a single value is simple enough to include here:

Not quite 1.0

The first obstacle to using fixed point arithmetic is the fact that our quantized values do not map 1:1. Many engines dequantize with code that looks like this (including Unreal 4 and ACL):

This is great in that it allows us to exactly represent both 0.0 and 1.0, we can support the full range we care about: [0.0 .. 1.0]. A case could be made to use a multiplication instead but it doesn’t matter all that much for the present discussion. With fixed point arithmetic we want to use all of our bits to represent the fractional part between those two values. This means the range of values we support is: [0.0 … 1.0). This is because both 0.0 and 1.0 have the same fractional value of 0 and as such we cannot tell them apart without an extra bit to represent the integral part.

In order to properly support our full range of values, we must remap it with a multiplication.

Fast coercion to float32

The next hurdle I faced was how to convert the fixed point number into a float32 value efficiently. I independently found a simple, fast, and elegant way and of course it turned out to be very popular for those very reasons.

For all of our possible values, we know their bit width and a shift can trivially be calculated to align it with the float32 mantissa. All that remains is or-ing the exponent and the sign. In our case, our values are between [0.0 … 1.0[ and thus by using a hex value of 0x3F800000 for exponent_sign, we end up with a float32 in the range of [1.0 … 2.0[. A final subtraction yields us the range we want.

Using this trick with the float32 implementation gives us the following code:

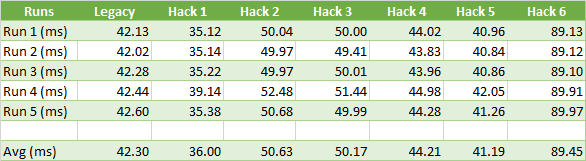

It does lose out a tiny bit of accuracy but it is barely measurable. In order to be sure, I tried exhaustively all possible sample and segment range values up to a bit rate of 16 bits per component. The up side is obvious, it is 14.9% faster!

32 bit vs 64 bit variants

Many variants were implemented: some performed the segment range expansion with fixed point arithmetic and the clip range expansion with float32 arithmetic and others do everything with fixed point. A mix of 32 bit and 64 bit arithmetic was also tried to compare the accuracy and performance tradeoff.

Generally, the 32 bit variants had a much higher loss of accuracy by 1-2 orders of magnitude. It isn’t clear how much this would impact the overall memory footprint on CMU and Paragon. The 64 bit variants had comparable accuracy to float32 arithmetic but ended up using more registers and more instructions. This often degraded the performance to the point of making them entirely uncompetitive in this synthetic test. Only a single variant came close to the original float32 performance but it could never beat the fast coercion derivative.

The fastest 32 bit variant is as follow:

Despite being 3 instructions shorter and using faster instructions, it was 14.4% slower than the fast coercion float32 variant. This is likely a result of pipelining not working out as well. It is entirely possible that in the real decompression code things could end up pipelining better making this a faster variant. Other processors such as those used in consoles and mobile devices also might perform differently and proper measuring will be required to get a definitive answer.

The general consensus seems to be that fixed point arithmetic can yield higher accuracy and performance but it is highly dependent on the data, the algorithm, and the processor it runs on. I can corroborate this and conclude that it might not help out all that much for animation compression and decompression.

Next steps

All of this work was performed in a branch that will NOT be merged into develop. However, some changes will be cherry picked by hand. In the short term, the conclusions reached here will not be integrated just yet into the main branches. The primary reason for this is that while I have extensive scripts and tools to track the accuracy, memory footprint, and compression performance; I do not have robust tooling in place to track decompression performance on the various platforms that are important to us.

Once we are ready, the fast coercion variant will land first as it appears to be an obvious drop-in replacement and some fixed point variants will also be tried on various platforms.

The accuracy issues will have to be fixed some other way and I already have some good ideas how: idea 1, idea 2, idea 3, idea 4, idea 5.