Controlling animation quality through streaming

17 Jan 2021For a few years now, I’ve had ideas on how to leverage streaming to further improve compression with the Animation Compression Library. Thanks to the support of NCSOFT, I’ve been able to try them out and integrate progressive quality streaming for the upcoming 2.0 release next month.

Progressive quality streaming is perfectly suited for modern games on high end consoles all the way down to mobile devices and web browsers. Its unique approach will empower animators to better control animation quality and when to pay the price for it.

Space is precious

For many mobile and web games out there, the size of animation data remains an ever present issue. All of this data needs to be downloaded on disk and later loaded into memory. This takes time and resources that devices do not always have in large supply. Moreover, on a small screen, the animation quality doesn’t matter as much as compression artifacts are often much less visible than on a large 4K monitor. Although it might seem like an ancient problem older consoles and early mobile phones had to worry about, many modern games still contend with it today.

A popular technique to deal with this is to use sub-sampling: take the key frames of an input animation clip and re-sample it with fewer key frames (e.g. going from 30 FPS to 24 FPS). Unreal Engine 4 implements a special case of this called frame stripping: every other key frame is removed.

By their nature, these techniques are indiscriminate and destructive: the data is permanently removed and cannot be recovered. Furthermore, if a specific key frame is of particular importance (e.g. highest point of a jump animation), it could end up being removed leading to undesirable artifacts. Despite these drawbacks, they remain very popular.

In practice, some data within each animation cannot be removed (metadata, etc) and as I have documented in a previous blog post, the animated portion of the data isn’t always dominant. For that reason, frame stripping often yields a memory reduction around 30-40% despite the fact that we remove every other key frame.

Bandwidth is limited

Animation data also competes with every other asset for space and bandwidth. Even with modern SSDs, loading and copying hundreds of megabytes of data still takes time. Modern games now have hundreds of megabytes of high quality textures to load as well as dense geometry meshes. These often have solutions to alleviate their cost both at runtime and at load time in the form of Levels of Details (e.g. mip maps). However, animation data does not have an equivalent to deal with this problem because animations are closer in spirit to audio assets: most of them are either very short (a 2 second long jump and its 200 millisecond sound effect) or very long (a cinematic and its background music).

Most assets that leverage streaming end up doing so in one of two ways: on demand (e.g. texture/mip map streaming) or ahead of time (e.g. video/audio streaming). Sadly, neither solution is popular with animation data.

When a level starts, it generally has to wait for all animation data to be loaded. Stalling and waiting for IO to complete during gameplay would be unacceptable and similarly playing a generic T-stance would quickly become an obvious eye sore. By their nature, gameplay animations can start and end at any moment based on player input or world events. Equally worse, gameplay animations are often very short and we wouldn’t have enough time to stream them in part (or whole) before the information is needed.

On the other hand, long cinematic sequences that contain lots of data that play linearly and predictably can benefit from streaming. This is often straightforward to implement as the whole animation clip can be split into smaller segments each compressed and loaded independently. In practice, cinematics are often loaded on demand through higher level management constructs and as such progressive streaming is not very common (UE4 does support it but to my knowledge it is not currently documented).

The gist

Here are the constraints we work with and our wish list:

- Animations can play at any time and must retain some quality for their full duration

- Not all key frames are equally important, some must always be present while others can be discarded or loaded later

- Most animations are short

- Large contiguous reads from disk are better than many small random reads

- Decompression must remain as fast as possible

Enter progressive quality streaming

Because most animations are short, it makes sense to attempt to load their data in bulk. As such, ACL now supports aggregating multiple animation clips into a single database. Important key frames and other metadata required to decompress will remain in the animation clip and optionally at runtime, the database can be provided to feed it the remaining data.

This leads us to the next question: how do we partition our data? How do we determine what remains in the animation clip and what can be streamed later? Crucially, how do we make sure that decompression remains fast now that our data can live in multiple locations?

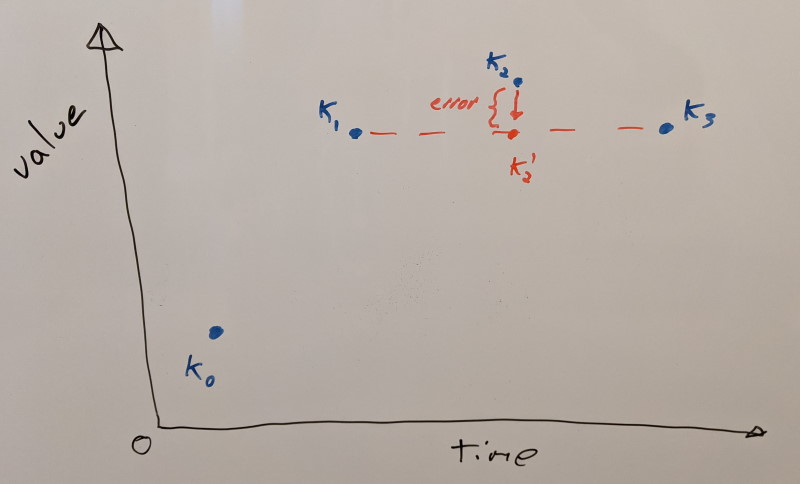

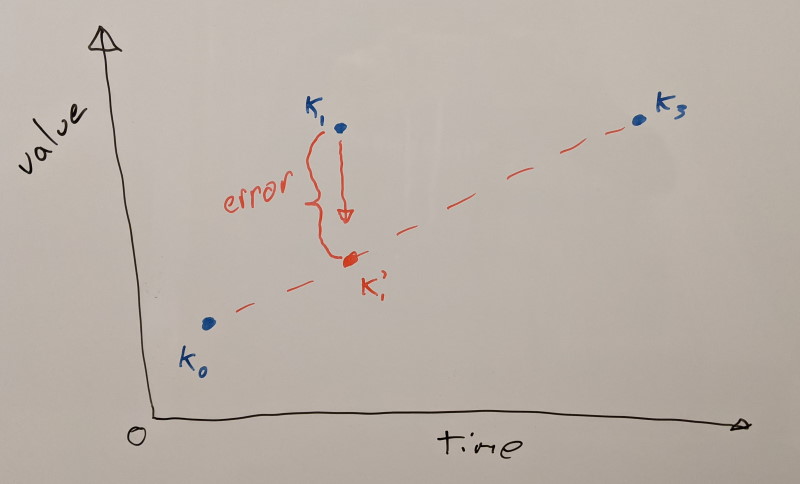

To solve this second part of the problem, during compression ACL will tag each whole key frame with how much error removing it contributes. We use this information to construct a variant of linear key reduction where only whole key frames are removed. However, in our case, they will simply be moved to the database instead of being lost forever. This allows us to quickly find the data we need when we sample our animation clip with a single search for which key frames we need. This helps keep the cost constant regardless of how many key frames or joints an animation clip has. By further limiting the number of key frames in a segment to a maximum of 32, finding the data we need boils down to a few bit scanning operations efficiently implemented in hardware.

The algorithm is straightforward. We first assume that every key frame is retained. We’ll pick the first that is movable (e.g. not first/last in a segment) and measure the resulting error when we remove it (both on itself and on its neighbors that might have already been removed). Any missing key frames are reconstructed using linear interpolation from their neighbors. To measure the error, we use the same error metric used to optimize the variable bit rates. We record how much error is contributed and we add back the key frame. We’ll iterate over every key frame doing so. Once we have the contributing error of every key frame, we’ll pick the lowest error and remove that key frame permanently. We’ll then repeat the whole process with the remaining key frames. Each step will remove the key frame that contributes the least error until they are all removed. This yields us a sorted list of how important they are. While not perfect and exhaustive, this gives us a pretty good approximation. This error contribution is then stored as extra metadata within the animation clip. This metadata is only required to build the database and it is stripped when we do so.

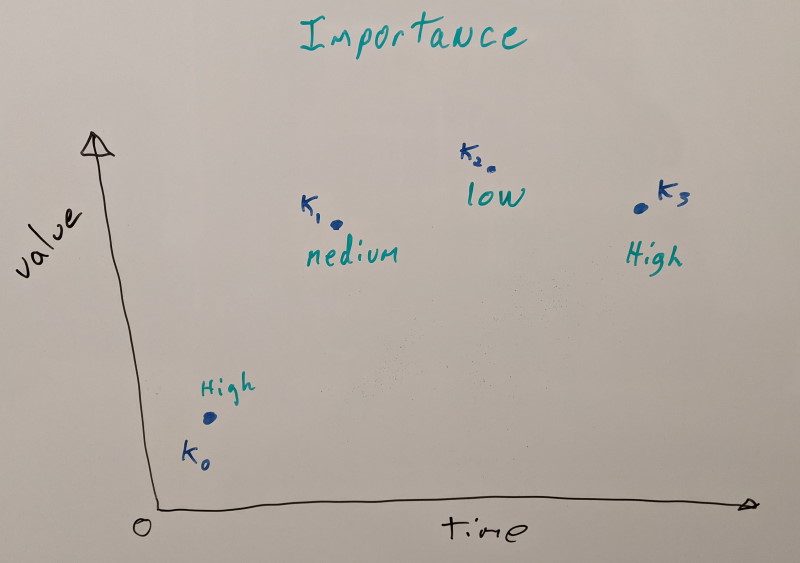

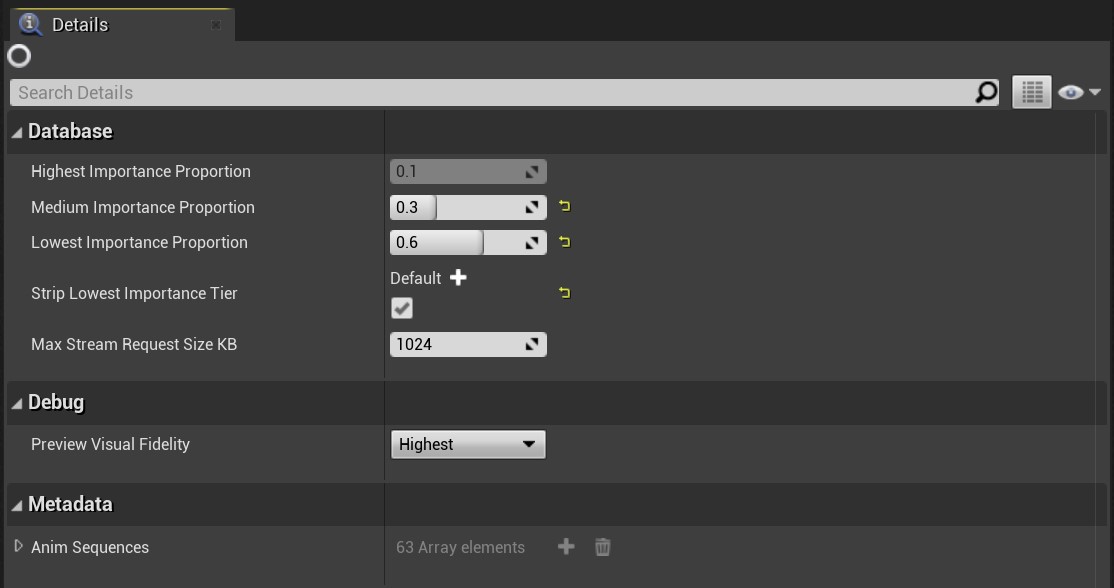

Now that we know which key frames are important and which aren’t, we’ll iterate over every animation clip and move the least important key frames out into the database first. Our most important key frames will remain within each animation clip to be able to retain some quality if we need to play back either with no database or with partial database data. How much data each tier will contain is user controlled and optionally the lowest tier can be stripped.

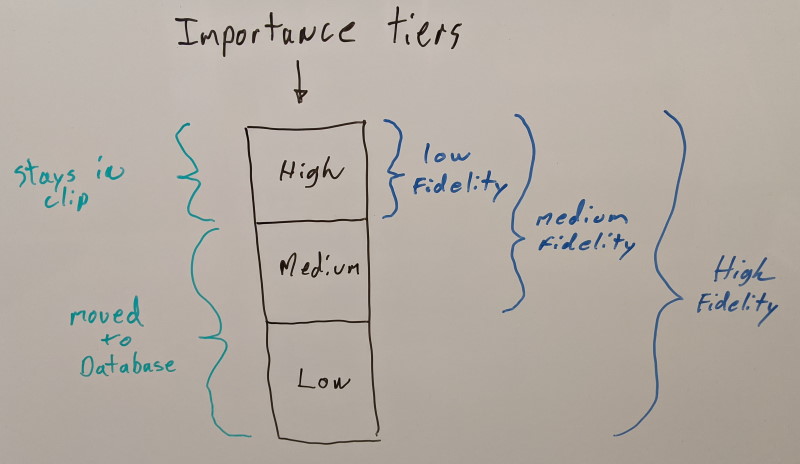

We consider three quality tiers for now:

- High importance key frames will remain in the animation clips as they are not optional

- Medium and low importance key frames are moved to the database each in its separate tier which can be streamed independently

Since we know every clip that is part of the database, we can find the globally optimal distribution. As such, if we wish to move the least important 50% percent, we will remove as much data as frame stripping but now the operation is far less destructive. Some clips will contribute more key frames than others to reach the same memory footprint. This is frame stripping on steroids!

This partitioning allows us to represent three visual fidelity levels:

- Highest visual fidelity requires all three importance quality tiers to be loaded

- Medium visual fidelity requires only the high and medium importance tiers to be loaded

- Lowest visual fidelity requires only the high importance tier to be loaded (the clip itself)

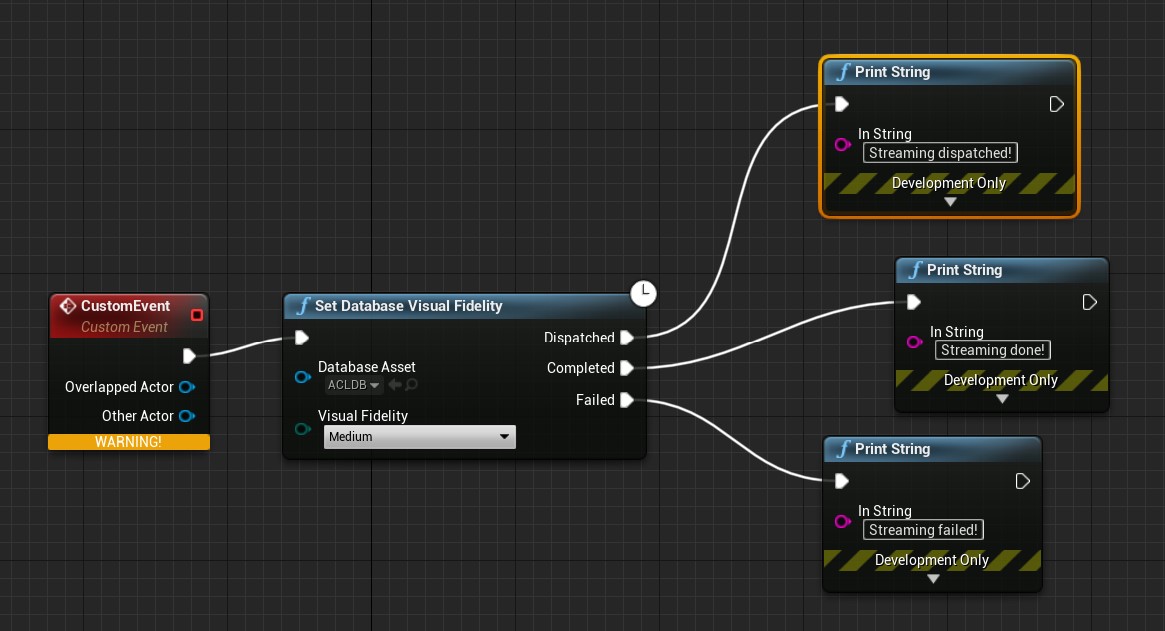

Under the hood, ACL allows you to stream both tiers independently and in any order you wish. For simplicity, the UE4 plugin exposes the desired visual fidelity level and the streaming request size granularity while abstracting what needs to stream in or out. This allows the game to allocate memory on demand when data is streamed in while also allowing the game to unload tiers that are no longer needed. In a pinch, the entire database can be unloaded or destroyed and animations can continue to play at the lowest visual fidelity level.

Unprecedented control

What this means is that you can now group animations into as many databases as makes sense for your game. Some animations always need the highest fidelity and shouldn’t belong to any database (e.g. main character locomotion) while general gameplay animations and exotic animations (e.g. emotes) can be split into separate databases for ultimate control. You can now decide at a high level how much data to stream later and when to stream it. Crucially, this means that you can decide ahead of time if a quality tier isn’t required and strip it entirely from disk or you can make that decision at runtime based on the device the game runs on.

You can make a single package for your mobile game that can run with reduced quality on lower end devices while retaining full quality for higher end ones.

Your multiplayer game can stream in the hundreds of emotes by grouping them by popularity lazily in the background.

Room to grow

Because the feature is new, I had to make a few executive decisions to keep the scope down while leaving room for future changes. Here are a few points that could be improved on over time.

I had to settle on three quality tiers both for simplicity and performance. Making the number arbitrary complicates authoring while at the same time might degrade decompression performance (which now only adds 100-150 instructions and 2 cache misses compared to the normal path without a database lookup). That being said, if a good case can be made, that number could be increased to five without too much work or overhead.

Evaluating how much error each key frame contributes works fine but it ends up treating every joint equally. In practice, some joints contribute more while others contribute less. Facial and finger joints are often far less important. Joints that move fast are also less important as any error will be less visible to the naked eye (see Velocity-based compression of 3D rotation, translation, and scale animations by David Goodhue about using velocity to compress animations). Instead of selecting the contributing error solely based on one axis (which key frame), we could split into a second axis: how important joints are. This would allow us to retain more quality for a given quality tier while reaching the same memory footprint. The downside though is that this will increase slightly the decompression cost as we’ll now need to search for four key frames to interpolate (we’ll need two for high and two for low importance joints). Adding more partitioning axes increases that cost linearly.

Any key frame can currently be moved to the database with two exceptions: each internal segment retains its first and last key frame. If the settings are aggressive enough, everything else can be moved out into the database. In practice, this is achieved by simply pinning their contributing error to infinity which prevents them from being moved. This same trick could be used to prevent specific key frames from being moved if an animator wished to author that information and feed it to ACL.

In order to avoid small reads from disk, data is split into chunks of 1 MB. At runtime, we specify how many chunks to stream at a time. This means that each chunk contains multiple animation clips. No metadata is currently kept for this mapping and as a result it is not currently possible to stream in specific animation clips as it would somewhat defeat the bulk streaming nature of the work. Should this be needed, we can introduce metadata to stream in individual chunks but I hope that it won’t be necessary. In practice, you can split your animations into as many databases as you need: one per character, per character type, per gameplay mode, etc. Managing streaming in bulk ensures a more optimal usage of resources while at the same time lowering the complexity of what to stream and when.

Coming soon

All of this work has now landed into the main development branches for ACL and its UE4 plugin. You can try it out now if you wish but if not, the next major release scheduled for late February 2021 will include this and many more improvements. Stay tuned!