Pitfalls of linear sample reduction: Part 2

25 Jul 2019A quick recap: animation clips are formed from a set of time series called tracks. Tracks have a fixed number of samples per second and each track has the same length. The Animation Compression Library retains every sample while the most commonly used Unreal Engine codecs use the popular method of removing samples that can be linearly interpolated from their neighbors.

The first post showed how removing samples negates some of the benefits that come from segmenting, rendering the technique a lot less effective.

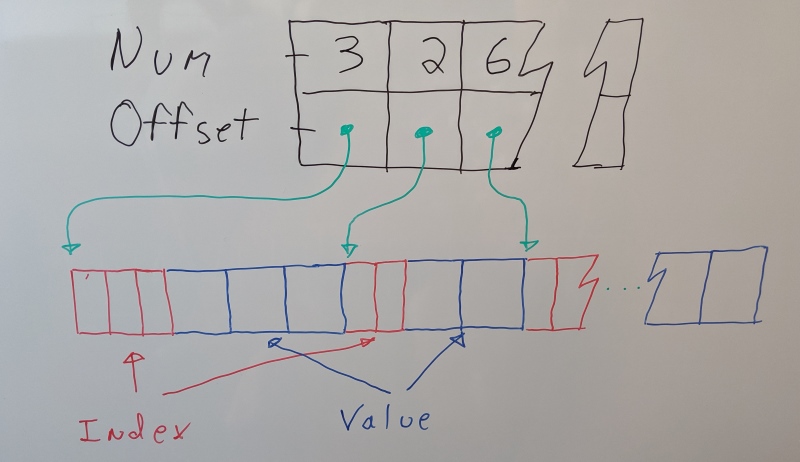

Another area where it struggles is decompression performance. When we want to sample a clip at a particular point in time, we have to search and find the closest samples in order to interpolate them. Unreal Engine lays out the data per track: the indices for all the retained samples are followed by their sample values.

This comes with a major performance drawback: each track will incur a cache miss for the sample indices in order to find the neighbors and another cache miss to read the two samples we need to interpolate. This is very slow. Each memory access will be random, preventing the hardware prefetcher from hiding the memory access latency. Even if we manage to prefetch it by hand, we still touch a very large number of cache lines. Equally worse, each cache line is only used partially as they also contain data we will not need. In the end, a significant portion of our CPU cache will be evicted with data that will only be read once.

In contrast, ACL retains every sample and sorts them by time (sample index). This ensures that all the samples we need at a particular point in time are contiguous in memory. Sampling our clip becomes very fast:

- We don’t need to search for our neighbors, just where the first sample lives

- We don’t need to read indices, offsets, or the number of samples retained

- Each cache line is fully used

- The hardware prefetcher will detect our predictable access pattern and work properly

Sorting is clearly the key to fast decompression.

Sorting retained samples

Back in 2017, if you searched for ‘‘animation compression’’, the most popular blog posts were one by Bitsquid which advocates using curve fitting with sorted samples for fast and cache friendly decompression and a post by Riot Games about trying the same technique with some success.

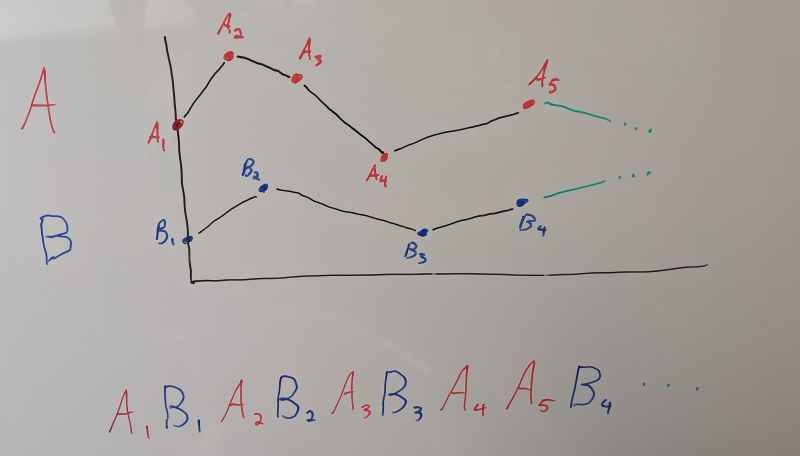

Without getting into the details too much (the two posts above explain it quite well), you sort the samples by the time you need them at (NOT by their sample time) and you keep track from frame to frame where and what you last decompressed from the compressed byte stream. Once decompressed, samples are stored (often raw, unpacked) in a persistent context object that is reused from frame to frame. This allows you to touch the least possible amount of compressed contiguous data every frame by unpacking only the new samples that you need to interpolate at the current desired time. Once all your samples are unpacked inside the context, interpolation is very fast. You can use tons of tricks like Structure of Arrays, wider SIMD registers with AVX, and you can easily interpolate two or three samples at a time in order to use all available registers and minimize pipeline stalls. This requires keeping a context object around all the time but it is by far the fastest way to interpolate a compressed animation because you can avoid unpacking samples that have already been cached.

Sorting our samples keeps things contiguous and CPU cache friendly and as such it stood to reason that it was a good idea worth trying. Some Unreal Engine codecs already support linear sample reduction and as such the remaining samples were simply sorted in the same manner.

With this new technique, decompression was up to 4x faster on PC. It looked phenomenal in a gym.

Unfortunately, this technique has a number of drawbacks that are either skimmed briefly, downplayed, or not mentioned at all in the two blog posts advocating it. Those proved too significant to ignore in Fortnite. Sometimes being the fastest isn’t the best idea.

No U-turn allowed

By sorting the samples, the playback direction must now match the sort direction. If you attempt to play a sequence backwards that has its samples sorted forward, you must seek and read everything until you find the ones you need. You can sort the samples backwards to fix this but forward playback will now have the same issue. There is no optimal sort order for both playback directions. Similarly, random seeks in a sequence have equally abysmal performance.

As Bitsquid mentions, this can be mitigated by introducing a full frame of data at specific intervals to avoid fully reading everything or segments can be used for the same purpose. This comes at the cost of a larger memory footprint and it does not offset entirely the extra work done when seeking. One would think that most clips play forward in time and it isn’t that big a deal. Sure some clips play backward or randomly but those aren’t that common, right?

In practice, things are not always this way. Many prop animations will play forward and backward at runtime. For example, a chest opening and closing might have a single animation played in both directions. The same idea can be used with all sorts of other objects like doors, windows, etc. A more subtle problem are clips that play forward in time but that do not start playing at the beginning. With motion matching, often when you transition from one clip to another you will not start playing the new clip at frame 0. When playback starts, you will have to read and skip samples, creating a performance spike. This can also happen with clips that advance in time but do not decompress due to Level of Detail (LOD) constraints. As soon as those characters start animating, performance spikes. It is also worth noting that even if you start playing at the first frame, you need to unpack everything needed to prime the context which creates a performance spike regardless.

30 FPS is ‘more cinematic’

It is not unusual for clips to be exported with varying sample rates such as 30, 60, or 120 FPS (and everything in between). Equally common are animations that play at various rates. However, unlike other techniques, these properties combine and can become problematic. If we play an animation faster than its sample rate (e.g. a 60 FPS game with 30 FPS animations) we will have frames where no data needs to be unpacked from the compressed stream and we can interpolate entirely from the context. This is very fast but it does mean that our decompression performance is inconsistent as some frames will need to unpack samples while others will not. This typically isn’t that big a deal but things get much worse if we play back slower than the sample rate (e.g. a 30 FPS game with 60 FPS animations). Our clip contains many more samples that we will not need to interpolate and because they are sorted, we will have to read and skip them in order to reach the ones we need. When samples are removed and sorted, decompression performance becomes a function of the playback speed and the animation sample rate. Such a problematic scenario can arise if an animation (such as a cinematic) requires a very high sample rate to maintain its quality (perhaps due to cloth and hair simulations).

Just one please

Although not as common, single bone decompression performance is pretty bad. Because all the data is mixed together, decompressing a specific bone requires decompressing (or at least skipping) all the other data. This is fine if you rarely do it or if it’s done at the same time as sampling the full pose while sharing the context between calls but this is not always possible. In some cases you have to sample individual bones at runtime for various gameplay or AI purposes (e.g. to predict where a bone will land in the future). This same property of the data means that lowering the LOD does not speed up seeking nor does it reduce the context memory footprint as everything needs to be unpacked just in case the LOD changes suddenly (although you can get away with interpolating only what you need).

One more byte

Just one more bite

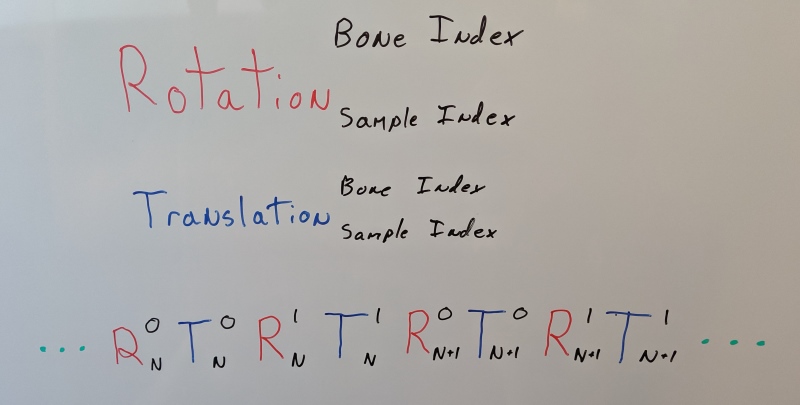

Sorting the samples means that there is no pattern to them and metadata per sample needs to be introduced. You need to be able to tell what type a sample is (rotation, translation, 3D scale, scalar), at what time the sample appears, and which bone it belongs to. This overhead being per sample adds up quickly. You can use all sorts of clever tricks to use fewer bits if the bone index and sample time index are small compared to the previous one but ultimately it is quite a bit larger than alternative techniques and it cannot be hidden or removed entirely.

With all of this data, the context object becomes quite large to the point where its memory footprint cannot be ignored in a game with many animations playing at the same time. In order to interpolate, you need at least two full poses with linear interpolation (four if you use cubic curves) stored inside along with other metadata to keep track of things. For example, if a bone transform needs a quaternion (rotation) and a vector3 (translation) for a total of 28 bytes, 100 bones will require 2.7 KB for a single pose and 5.5 KB for two (and often 3D scale is needed, adding even more data). With curves, those balloon to 11 KB and by touching them you evict over 30% of your CPU L1 cache (most CPUs have 32 KB of L1) for data that will not be needed again until the next frame. This is not cheap.

It is clear that while we touch less compressed memory and avoid the price of unpacking it, we end up accessing quite a bit of uncompressed memory, evicting precious CPU cache lines in the process. Typically, once decompression ends, the resulting pose will be blended with another intermediate pose later to be blended with another, and another. All of these intermediate poses benefit from remaining in the cache because they are needed over and over often reused by new decompression and pose blending calls. As such, the true cost of decompression cannot be measured easily: the cache impact can slow down the calling code as well. While sorting is definitely more cache friendly than not doing so when samples are removed, whether this is more so than retaining every sample is not as obvious.

You can keep the poses packed in some way within the context, either with the same format as the compressed stream or packed in a friendlier format at the cost of interpolation performance. Regardless, the overhead adds up and in a game like Fortnite where you can have 50 vs 50 players fighting with props, pets, and other things animating all at the same time, the overall memory footprint ended up too large to be acceptable on mobile devices. We attempted to not retain a context object per animation that was playing back, sharing them across characters and threads but this added a lot of complexity and we still had performance spikes from the higher amount of seeking. You can have a moderate amount of expensive seeks or a lower runtime memory footprint but not both.

This last point ended up being an issue even without any sorting (just with segmenting). Even though the memory overhead was not as significant, it still proved to be above what we would have liked, the complexity too high, and the decompression performance too unpredictable.

A lot of complexity for not much

Overall, sorting the samples retained increased slightly the compressed size, it increased the runtime memory footprint, decompression performance became erratic, while peak decompression speed increased. Overcoming these issues would have required a lot more time and effort. With the complexity already being very high, I was not confident I could beat the unsorted codecs consistently. We ultimately decided not to use this technique. The runtime memory footprint increased beyond what we considered acceptable for Fortnite and the decompression performance too erratic.

Although the technique appeared very attractive as presented by Bitsquid, it ended up being quite underwhelming. This was made all the more apparent by my parallel efforts with ACL that retained every sample yet achieved remarkable results with little to no complexity. ACL has consistent and fast decompression performance regardless of the playback rate, playback direction, or sample rate and it does this without the need for a persistent context.

When linear sample reduction is used, both sorted and unsorted algorithms have significant drawbacks when it comes to decompression performance and memory usage. While both techniques require extra metadata that increases their memory footprint, if enough samples are removed, the overhead can be offset to yield a net win. The next post will look into how many samples need to be removed in order to beat ACL which retains all of them.