Animation Compression Library: Release 0.4.0

10 Sep 2017This marks the fourth release of ACL. It contains a lot of good stuff but most notable is the addition of segmenting support. I have not had the chance to play with the settings much yet but using segments of 16 key frames reduces the memory footprint by about 13% with variable quantization under uniform sampling. Adding range reduction on top of it (per segment), further reduces the memory footprint by another 10%. This is very significant!

Some optimizations also made it in to the compression time, reducing it by 4.3x with no compromise to quality.

You can see the latest numbers here as well as how they compare against the previous releases here. Note that the documentation contains more graphs than I will share here.

This also represents the first release where graphs have been generated allowing us an unprecedented view into how the ACL and Unreal algorithms perform. As such, I will detail what is note-worthy and thus this blog post will be a bit long. Grab a coffee and buckle up!

TL;DR:

- ACL compresses better than Unreal for nearly every clip in the CMU database.

- ACL is much smaller than Unreal (23.4%), is more accurate (2x+), and compresses much faster (4.68x).

- ACL performs as expected and optimizes properly for the error threshold used, validating our assumptions.

- A threshold of 0.1cm is good enough for production use in Unreal as the overwhelming majority (98.15%) of the samples have an error smaller than 0.02cm.

Why compare against Unreal?

As I have previously mentioned, Unreal 4 has a very solid error metric and good implementations of common animation compression techniques. It most definitely is well representative of the state of animation compression in game engines everywhere.

NOTE: In the images that follow, the results for an error threshold of UE4 @ 1.0cm were nearly identical to 0.1cm and were thus omitted for brevity

Performance results

ACL 0.4 compresses the CMU database down to 82.25mb in 50 minutes single-threaded and 5 minutes multi-threaded with a maximum error of 0.0635cm. Unreal 4.15 compresses it down to 107.94mb in 3 hours and 54 minutes single-threaded with a maximum error of 0.0850cm (1.0cm threshold used). Importantly, this is achieved with no compromise to decompression speed (although not yet measured, is estimated to be faster or just as fast with ACL).

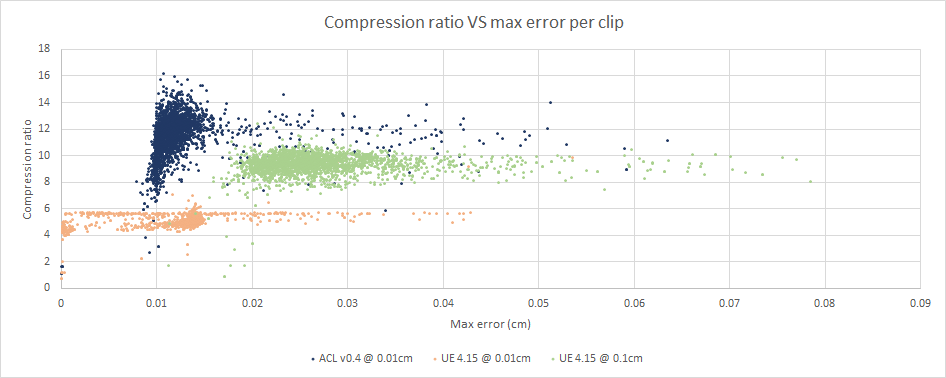

As can be seen on the above image, ACL performs quite well here. The error is very low and the compression quite high in comparison to Unreal.

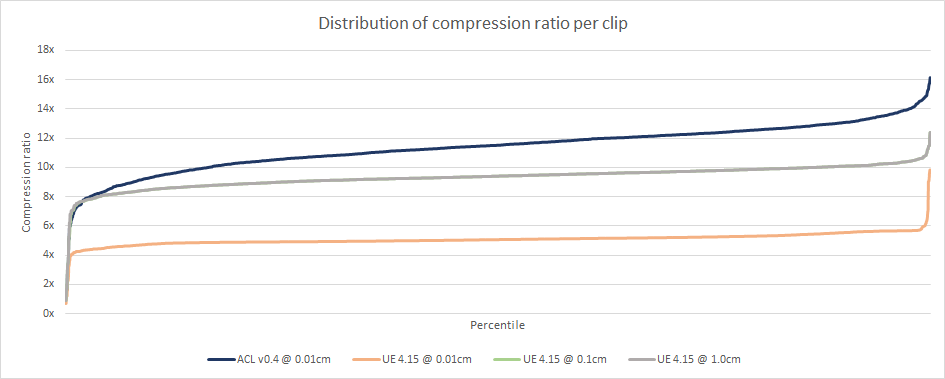

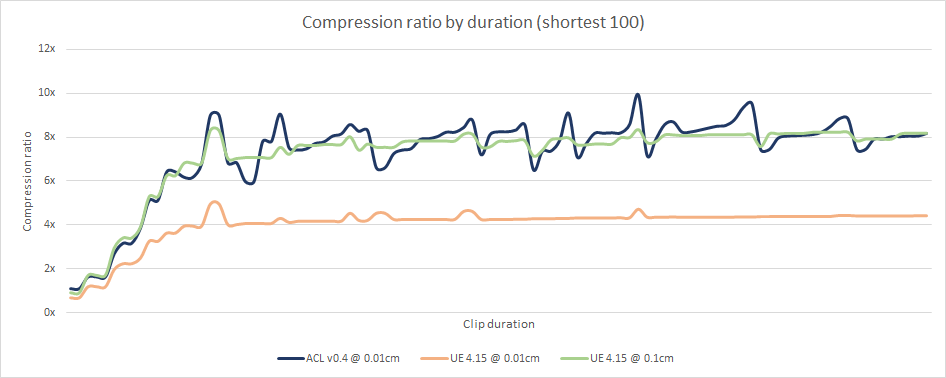

Here we see the full distribution of the compression ratio over the CMU database. UE4 @ 0.01cm fails to do better than dropping the quaternion W and storing everything as full precision most of the time which is why the compression ratio is so consistent. UE4 @ 0.1cm performs similarly in that key reduction fails very often on this database and as a result simple quantization is most often selected.

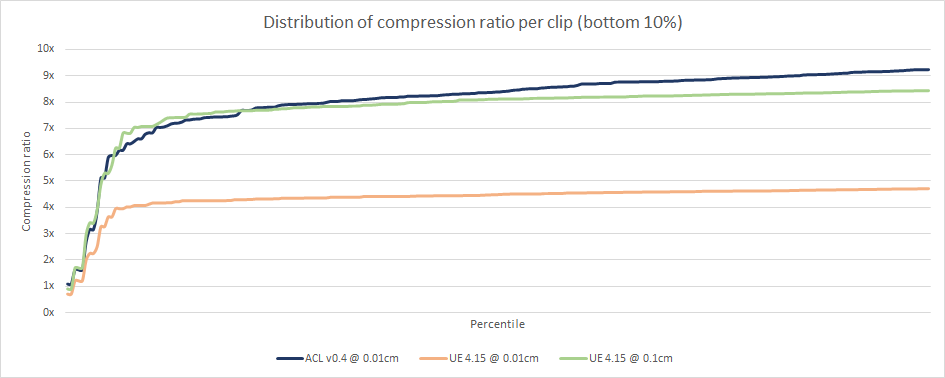

Here is a snapshot of the bottom 10% (10th percentile and lower). We can see some similarities in shape at the bottom and top 10%.

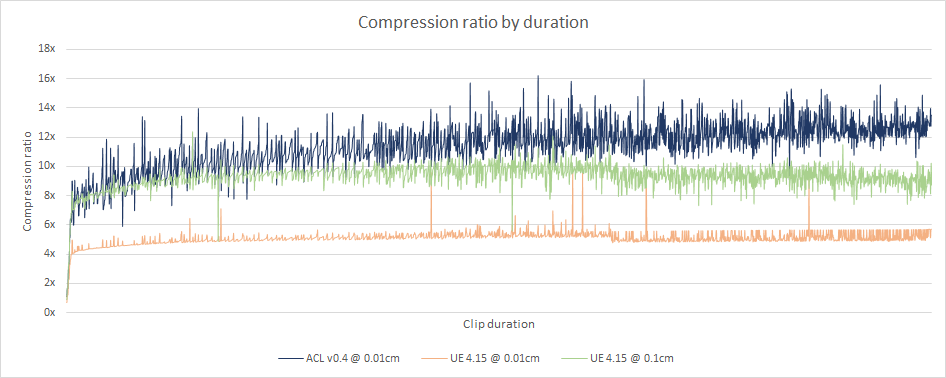

We can see on the above image that Unreal performs consistently regardless of the animation clip duration but ACL performs slightly better the longer the clip is. This is most likely a direct result of using range reduction twice: once per clip, and once per segment.

Both algorithms perform similarly for the shortest clips.

How accurate are we?

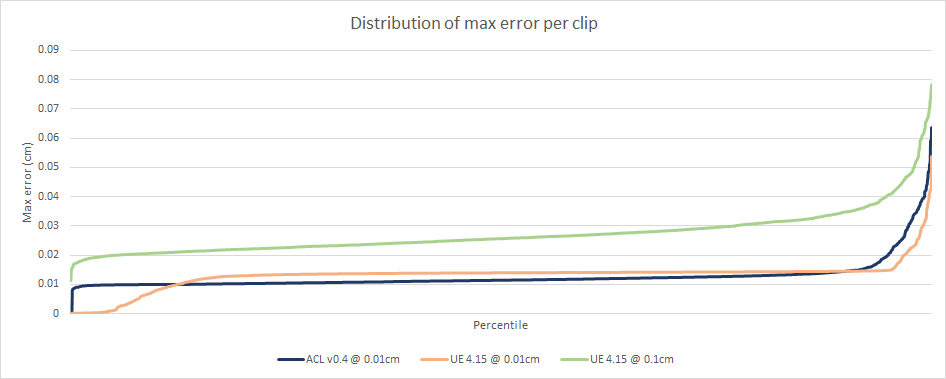

The above image gives a good view of how accurate the algorithms are. We can see ACL @ 0.01cm and UE4 @ 0.01cm quickly reach the error threshold and only about 10% of the clips exceed it. UE4 @ 0.1cm is less accurate but still pretty good overall.

The biggest source of error in both ACL and Unreal comes from the usage of the simple quaternion format consisting of dropping the W component to later reconstruct it at runtime. As it turns out, this is terribly inaccurate when that component is very small. Better formats exist and will be implemented later.

ACL performs worse on a larger number of clips likely as a result of range reduction sometimes causing a precision loss for some clips. At some point ACL should be able to detect this and turn it off if it isn’t needed.

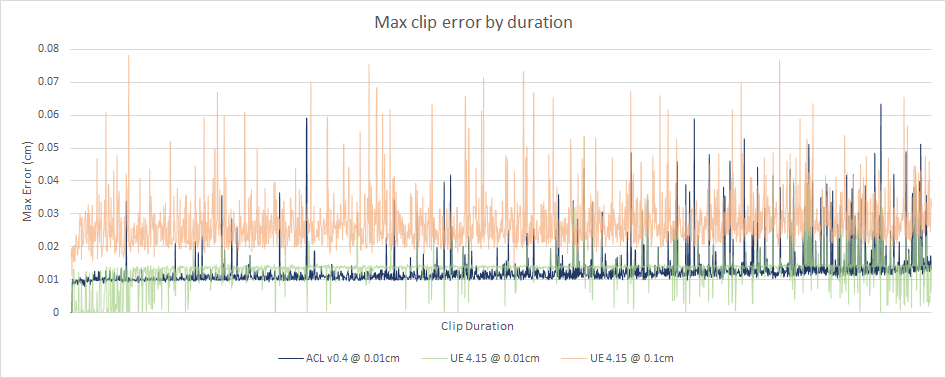

There does not appear to be any correlation between the max error in a clip and its duration, as expected. One thing stands out though, the longer a clip is, the noisier the error appears to be. This is because the longer a clip is the more likely it is to contain a bad quaternion W that fails to reconstruct properly.

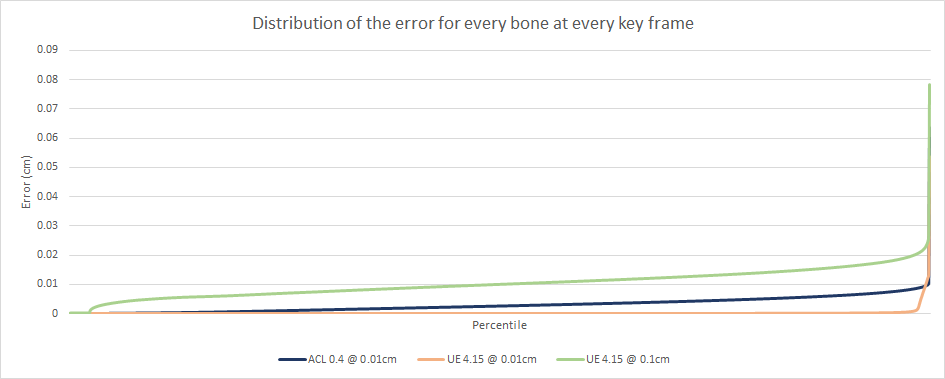

Over the years, I’ve read my fair share of animation compression papers and posts. And while they all measure the error differently the one thing they have in common is that they only talk about the worst error within a clip (or whole set of clips). As I have previously mentioned, how you measure the error is very important and must be done carefully but that is not all. Using the worst error within a given clip does not give a full picture. What about the other bones in the clip? What about the other key frames? Do I have a single bone on a single key frame that violates my threshold or do I have many?

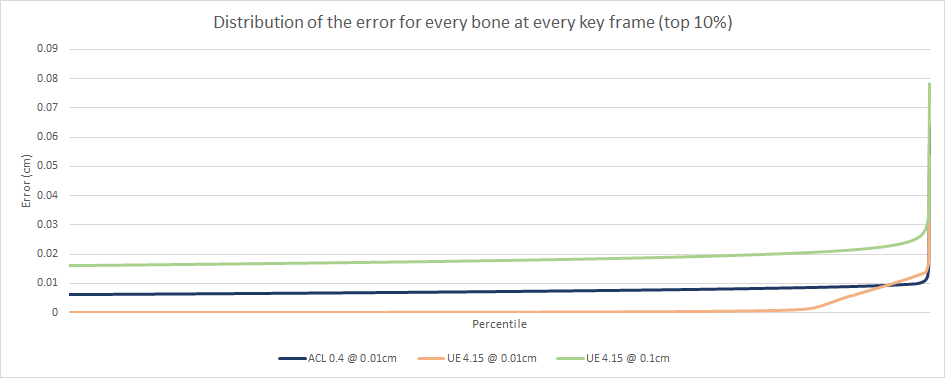

In order to get a full and clear picture, I dumped the error of every bone at every key frame in the original clips. This represents over 37 million samples for the CMU database.

The above image is amazing!

The above two images clearly show how terrible the max clip error is at giving insight into the true error. Here are some numbers visible only in the exhaustive graphs:

- ACL crosses the 0.01cm error threshold at the 99.85th percentile (only 0.15% of our values exceed the threshold!)

- UE4 @ 0.01cm crosses 0.01cm at the 99.57th percentile, almost just as good

- UE4 @ 0.1cm crosses 0.01cm at the 49.8th percentile

- UE4 @ 0.1cm crosses 0.02cm at the 98.15th percentile

This clearly shows why 0.1cm might be good enough for production use in Unreal: half our values remain at or below 0.01cm and 98% of the values are below 0.02cm.

The previous images also clearly show how aggressive ACL is at reducing the memory footprint and at maximizing the error up to the error threshold. Therefore, the error threshold must be very conservative, much more so than for Unreal.

Why ACL is re-inventing the wheel

As some have commented in the past, ACL is largely re-inventing the wheel here. As such I will detail the rational for it a bit further.

Writing a whole animation blending middleware such as Granny or Morpheme would not have been practical. Just to match production quality implementations out there would have taken 1+ year part time. Even assuming I could have managed to implement something compelling, the cost of switching to a new animation runtime for a game team is very very high. Animators need to learn new tools and workflow, the engine integration might be tightly coupled, and there is no clear way to migrate old assets to the new format. Middlewares are also getting deprecated increasingly frequently. In that regard, the market has largely spoken: most games released today do so either with one of the major engines (Unreal, Unity, Lumberyard, Stingray, etc.) or large studios such as Activision, Electronic Arts, and Ubisoft routinely have in-house custom engines with their own custom animation runtime. Regardless of the quality or feature set, it would have been highly unlikely that it would ever have been used for something significant.

On the other hand, animation compression is a much smaller problem. Integration is easy: everything is pure C++ headers and most engines out there already support more than one animation compression algorithm. This makes migrating existing assets a trivial task providing the few required features are supported (e.g. 3D scale). Any engine or middleware could integrate ACL with few to no issues to be expected once it is production ready.

Animation compression is also a wheel that NEEDS re-inventing. Of all my blog posts, a single post receives the overwhelming majority of my traffic: animation compression in Unity. Why is it so popular? Because as I mention in said post, accuracy issues will be common in Unity and the memory footprint large for high accuracy settings as a direct result of their error metric. Unity is also not alone, Stingray and Lumberyard both use the same metric. It is a VERY common error metric and it is terrible. Academic papers on this topic are often using different and poor error metrics and show very little to no data to back their results and claims. This makes evaluating these papers for real world usage in games very problematic.

Take this paper for example. They use the CMU database as well. Their error metric uses the leaf bone positions in object/world space as a measure of accuracy. This entirely ignores the rotational error of the leaf bone. They show a single graph of their results and two short tables. They do not detail the data further. Compare this with the wealth of information I was able to pull out and publish here. Even though ACL is much stricter when measuring the error, it is obvious that wavelets fail terribly to compete at the same level of accuracy (which barely makes it in their published findings). Note that they make no mention of what is an acceptable quality level that one might be able to realistically use.

Here is another recent paper published by someone I have met and have great respect for. The paper does not mention which error metric was used to compared against what they had prior nor does it mention how competitive their previous implementation was. It does not publish any concrete data either and only claims that the memory footprint reduces by 65% on average against their previous in-house techniques. It does provide a supplemental video which shows a small curated list of clips along with some statistics but without further information, it is impossible to objectively evaluate how it performs and where it lies on the spectrum of published techniques. Despite these shortcomings, it looks very promising (David knows his stuff!) and I am certainly looking forward to implementing this within ACL.

ACL does not only strive to improve on existing techniques; it will also establish a much-needed baseline to compare against and set a standard for how animation compression should be measured.

Next steps

The results so far clearly show that ACL is one step closer to being production ready. The next few months will focus on bridging that gap towards reaching v1.0.0. In the coming releases, scale support will be added as well as support for other leading platforms. This will be done through a rudimentary Unreal 4 integration to make sure it is tested in a real engine and thus real world settings.

No further effort on my part will be made towards improving the above results until our first production release is made. However, Cody Jones is working on integrating curve key reduction in the meantime.

Special thanks to Cody and Martin Turcotte for their constant feedback and contributions!