Animation Compression: Preface

25 Oct 2016This post is meant as a preface to explain the overall context of what is character animation, how we use it, and why it needs special consideration.

This series of posts will only cover the compression aspect of animation data, we will not look into everything else that goes into writing an animation runtime library such as Morpheme.

Modern character animation

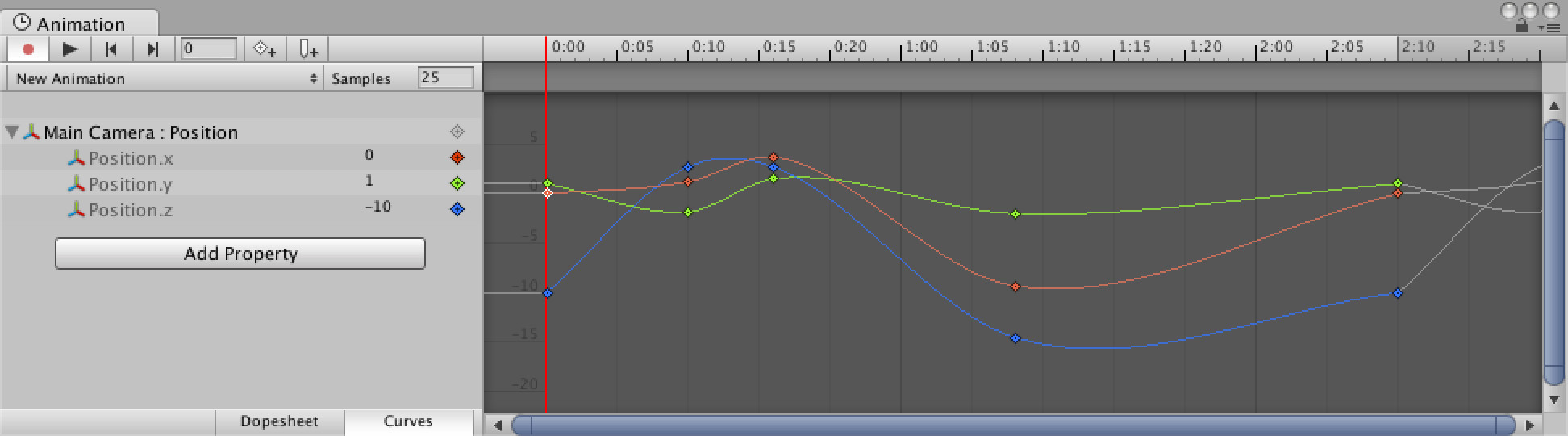

For the purpose of this series, we will only refer to character animation sequences that play back over a rigid skeleton (also called a rig). In Maya (and other similar products), an animator will typically author the animation sequence from a set of curves by manipulating the skeleton to achieve the desired motion.

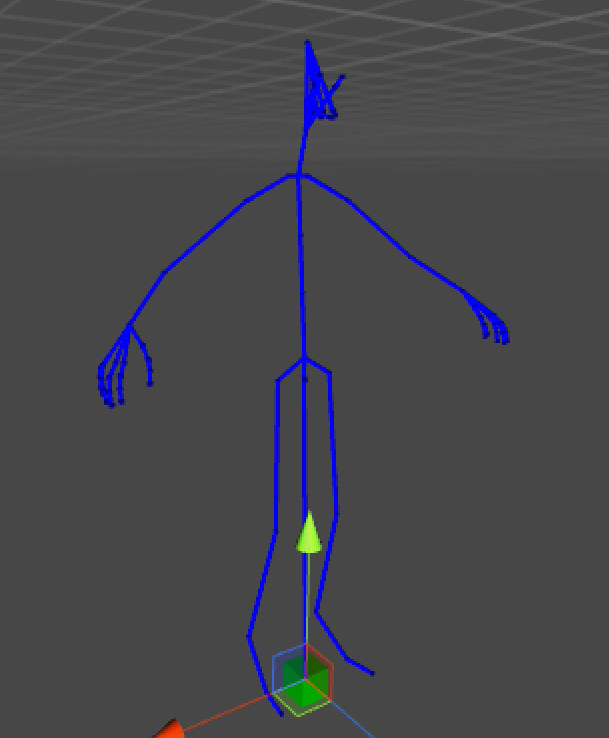

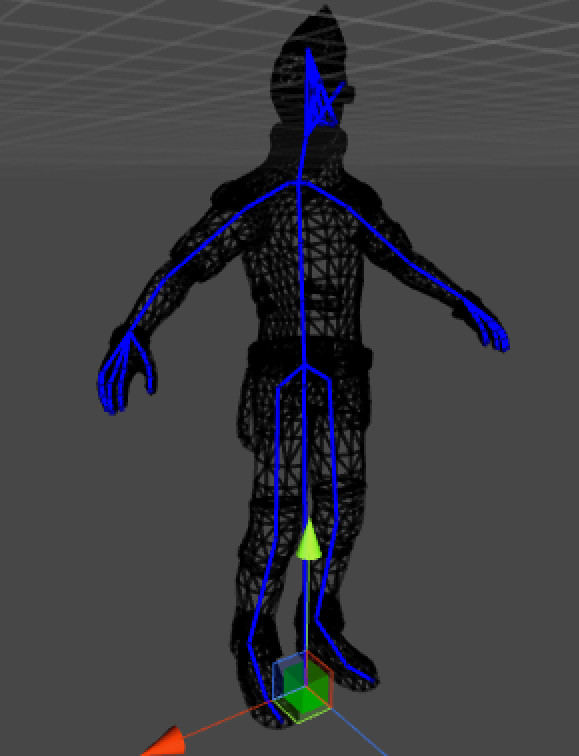

This information is used at runtime to animate the rigid skeleton which in turn deforms the visual mesh bound to it. Note that animation sequences can be authored in 3 main ways: by hand, from motion capture, or procedurally (for example, a cloth simulation).

Central to all this is our rigid skeleton. The skeleton is composed of a number of bones, typically in the range of 100-200 for main characters (but this number can be much larger, up to 1000 in some cases). Some of these will almost always be animated (such as the pelvis), some are animated procedurally at runtime and thus never authored, while others are only animated in a small subset of animations such as facial bones.

The actual process to generate the final skeleton pose will vary but it generally involves blending a number of animation sequences together. The number of poses blended will vary greatly at runtime, and for a main character it can often range from 6 to 20 poses. Although an interesting topic, we will not go into further detail.

The final visual mesh deformation process is commonly referred to as ‘skinning’. Depending on the video game engine, skinning is typically done either by interpolating 4x4 matrices or dual quaternions. The former is the most common but can yield some artifacts while the later approach is the mathematically correct way to do skinning. Both have their pros and cons but we will not go further into detail since it is not immediately relevant to our topic at hand.

How is it used in AAA video games?

For a long time now (at least since the original PlayStation), 3D character animation has been used by a large array of video game titles. Over time the techniques used to author the animation sequences have evolved and the amount of content has gradually crept up. Today, it isn’t unusual for a AAA video game to have several thousands of individual character animations.

Animation sequences are used for all sort of things beyond just animating characters: they can animate cameras, vegetation, animals or critters, objects (e.g. door, chest), etc.

As a result of this, it is not unusual to end up having between 20-200MB worth of animations at runtime. On disk, the size is of course even larger.

Its unique requirements

To generate a single image (or frame), it is not uncommon to end up sampling over 100 animation sequences. As such, it is critically important for this operation to be very fast. Typically on a modern console, we are targeting 50-100us or lower to sample a single sequence.

Due to the large amount of animation sequences, it is also very important for their size to remain small. This is both important on disk, which impacts our streaming speed, and in memory, which impacts the maximum amount of sequences we can hold.

As we will see later, not all animation sequences are created equal, as some will require higher accuracy than others.

These things must all be taken into account when designing or selecting a compression algorithm. The compression algorithms we will be discussing will all be lossy in nature as that is the most common industry practice.

Note: All images taken from Unity 5